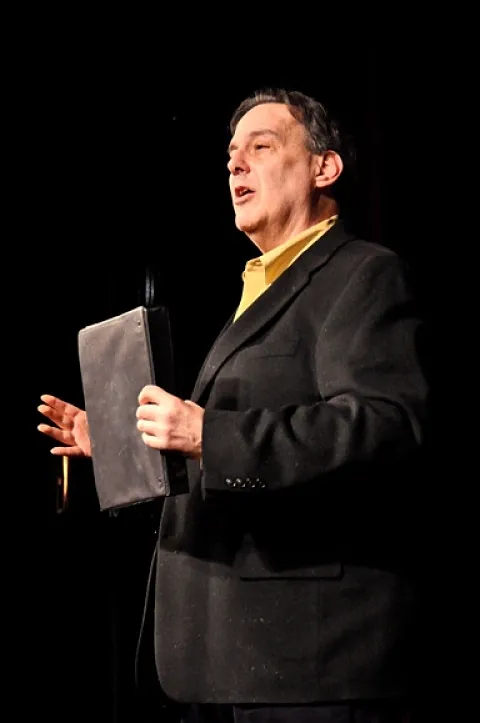

Michael Earl Feingold (1945-2022)

Reflections on a Life

(Photo by Genevieve Rafter Keddy, American Theatre Magazine)

(Photo by Genevieve Rafter Keddy, American Theatre Magazine)

More than half a century ago, Michael Feingold served as the first Literary Manager of the Yale Repertory Theater. (The title was borrowed from a few of his few predecessors: Kenneth Tynan at the National and John Lahr at Lincoln Center. “Dramaturg” was not yet in much use.) He later served in similar positions at the Guthrie and the American Repertory Theater. Of course, Michael was better known as a critic and translator, but as a dramaturg he was truly a trailblazer. I had the honor of being his assistant and, a couple of times, his successor. I learned a great deal from him, which wasn’t hard; he was one of the smartest, most knowledgeable people I ever met. At an early age, and until the end, Michael Feingold was a curmudgeon, but he was also an enthusiast. He loved the theater and its people, and many of us have benefited profoundly from crossing his path.

Jonathan Marks

When I was still in New Haven working on my DFA, there was a curious sequence of talks followed by lunches of theater folk that Feingold curated for the Theater Management MFA students. I particularly remember having lunch with Michael and René Buch from Repertorio Español. They were both warm and witty, quite welcoming to a young dramaturg they didn’t know from Adam.

Adam Nathaniel Versenyi

I was fortunate to work with Michael Feingold when he was commissioned to do a translation at the Empty Space Theater in the early 1990s. Since those days, I've heard many stories about him — both good and bad. All I can say for certain is my own experience. I was touched by how closely and well he listened to a young dramaturg who's fluent in German and had experience translating. I was scared to approach him, but he complimented me and listened to me, recognized my gifts and gave me confidence. Yes, I was helping HIM too — but he wasn't too egotistical or high up to realize that I had some good stuff to share (as some others were!), and I'll always be grateful for that!

Susan Russell

I met Michael Feingold when I was 14, and we became lifelong friends. I knew his whole family (even his cousins) and he knew mine. I am a theater critic and occasional dramaturg because of Michael. I'll let others praise Michael’s professional accomplishments, astonishing mind and genuine warmth (once you got to know him). I can better serve his memory with several personal anecdotes:

"Agamemnon, neenee-nahnah-noonoo! Oh! Oh! Oh!" Thus laments the chorus in the obscure Greek tragedy, Elarktra, concerning bird poop on the head of a heroic statue. Remarkably, this nearly lost theatrical classic was uncovered by a 16-year-old; an age when most of us neither knew what Greek tragedy was, nor had read one. That precocious 16-year-old was Feingold, writing a skit — in verse, no less — for the student variety show at Highland Park High School. Translating Brecht? No sweat!

In the early 1980s, Michael helped his friends, Alvin Epstein and Martha Schlamme, compile a revue of theater songs, which they successfully performed around the country. Due to the composers featured in the revue, Michael puckishly proposed they call it Bernstein, Blitzstein, Epstein and Schlamme. He lost.

I called Michael the day after 9/11. He lived on the Upper West Side, but you never know. Thankfully, Michael was fine. The day before, he told me, he had been at a friend's apartment on

West End Avenue. “We stood on the balcony and watched the ambulances race up to Roosevelt Hospital. We said ‘Kaddish.’ What else could we do?”

Jonathan Arbabanel

My dear friend is gone. It hurts. And I remember what fun Michael Feingold was, how challenging, interesting, and deeply amusing he could be. We trusted each other enough to say anything, yet we didn’t tell each other everything. Michael enjoyed my company, and I his, without limiting it by labelling it. Michael (never Mike!) and I met in one of Robert Brustein’s Modern Drama classes at Columbia. When we graduated in 1966, we both headed to Yale Drama School. Bob Brustein had just become its Dean. Michael and I became Brustein’s T.A.s in the drama classes he taught to Yale undergrads. At first, Michael and I sat together, commenting on Bob’s lectures, the students’ body language, and Broadway shows, exchanging pungent remarks on them all. It didn’t take long for Bob Brustein to order us to sit separately. In later years, Michael and I saw many plays and a few movies together. His reviews in The Village Voice and elsewhere were always thoughtful and often revelatory. Michael never confused a play’s popularity with its quality. You could trust him. One story among many: When I translated Jarry’s Ubu Roi, I was stuck on how to turn Jarry’s word “Palotins” for Pa Ubu’s soldiers into English. I tried “Palcontents,” but it felt too cutesy, not dangerous enough. Then Michael suggested “Frigadiers.” You know that moment when things just get nailed? What a gift Michael Feingold was. What a gift he is.

David Copelin

When I arrived in New York in the late Sixties, Off-off-Broadway was well under way. Caffe Cino was on the verge of closing, but La Mama, the Albee-Barr-Wilder Playwrights Unit, and the theater in the Judson Church on Washington Square were all putting up new stuff. Other companies – including one I followed with special enthusiasm, Circle Rep – were just about to be born. And the O’Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut was just hitting its stride as an incubator of new writers and writing.

Playwright John Guare (who began his career working in these small venues) remembered that there was something like a war going on between these mostly downtown operations and the commercial/establishment theater of Broadway. Part of the war was based on the fact that Off-off-Broadway cheerfully engaged subject matter and language (and nudity) that the uptown crowd wouldn’t touch.

The Village Voice was an active chronicler of this war, and not an objective one. It was firmly on the side of the insurgents. There was an extraordinary team of drama critics (yes, white and male) covering the action. Occasionally one of them would venture to Broadway and mostly snort with derision at the shallow crap there. (Not all of it was shallow crap, of course.) But the Voice’s main interest was in offering a running account of what was happening in the smaller venues. And the chief critic engaged in this work was Michael Feingold.

OK, I’ve finally gotten to his name. But I had to set the stage for him. Because his stage was indeed these stages. If we identify Kenneth Tynan as the chief chronicler of the change in postwar British theater and Richard Christiansen as the one who gave us a ringside seat to the extraordinary renaissance of Chicago theater, I think we should identify Michael as the most enthusiastic and fecund critic covering Off-off-Broadway.

I was beginning to wade into these waters myself. Though I am primarily a playwright, I stumbled into a side career writing about the theater. Otis L. Guernsey, Jr., the editor of the Best Plays Annual, viewed the invaders from downtown with some apprehension and decided to install me as a firewall. He knew off-off-Broadway had to be covered, but he didn’t want to hear the F-words and he preferred his actors clothed, so he assigned me to cover off-off-Broadway so he wouldn’t have to.

And I looked to Michael for guidance. Reading him was part of my education. He offered me a pathway to understanding work that aspired to something beyond the easy accessibility of the work that came out of the Broadway machines. He also flagged the rising artists to whom I should give my attention.

I can’t say I remember when we first met. Probably either in a theater lobby or at the O’Neill Center. But I do remember hanging back and listening to discussions he was part of. Almost inevitably, after someone had put forward a point, Michael would respond with, “Ah yes, but ...” And the “but” almost always re-framed the discussion with some historical tidbit or some subtle insight that had occurred to none of the rest of us.

I gradually realized that though he was an advocate of the new, nobody of my acquaintance had a deeper familiarity with theater history. I remember reading him on one of the several productions of Long Day’s Journey Into Night that he covered. I can’t recall which revival it was, but he described the relationship of the four leading characters as a knot comprised of love and resentment – and he traced each individual strand in a way that suddenly revealed the heart of the play for me.

I got to know him better when I got the assignment to write The O’Neill, a history of the Eugene O’Neill Memorial Theater Center. He was part of that history in several roles – as a dramaturg, as a member of the faculty of the National Critics Institute, and as a playwright. My job was to collect stories that made vivid the evolution of the place. I think he once said that he’d spent 20 summers there. Consequently, he was the source for more anecdotes in the book than anybody else. He brought particular insight into the Playwrights Conference’s artistic director, Lloyd Richards, describing his genius for turning conflict into dialogue and collegiality. It helped that Michael seemed to remember everybody who attended the conferences when he was present, and he remembered not only the plays but the tensions behind the often difficult process of bringing scripts by young, unformed talents to the Spartan stages in staged readings.

As was reported in the Times obit, Michael himself was the subject of one of the best of the stories. He was assigned to work with Bill Partlan on a manuscript that some on the staff referred to as a telephone book because of its size. It was the first version of August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom and, in its initial reading, it ran something like four hours. Partlan told me (and I found independent sources that quoted Wilson to confirm) that Michael was key to helping Wilson make cuts that would shorten the play but maintain its integrity. There were two performances of Ma Rainey at the O’Neill. The first was the uncut version. The second was the considerably shorter one that Michael and Partlan helped Wilson find. It was that version that a visiting critic from the New York Times, Frank Rich, was so impressed by that he bent protocol (O’Neill presentations weren’t supposed to be reviewed) to praise, launching Wilson’s career.

Michael lived in my neighborhood, and, in the wake of the release of my book, he allowed that I might be worthy company for the occasional lunch. It struck me that he was our generation’s Alexander Woollcott. (I’m talking about the real Woollcott, not the amiable caricature we know from Kaufman and Hart.) He wasn’t a sentimentalist like Woollcott, but he had Woollcott’s delight in verbal play, and he had Woollcott’s ability to apply his extraordinary memory to immediate concerns. And I think, like Woollcott, he constructed a persona that he could play in the company of others that relieved him from revealing much that was genuinely private.

As pleased as I was by the space the New York Times accorded his obit, I understood the irritation a few of his colleagues expressed that so much emphasis was placed on the showier, more combative side of his writing. He could be funny in his dismissals of what he thought was dross (e.g., Miss Saigon), but, though he could certainly get off a good line, he found his deepest satisfaction in celebrating and educating. It was rare when we were discussing something at the Manhattan Diner that he didn’t add, “Ah, but now you must take a look at ...”

Jeffrey Sweet

Many of those who have already written tributes about Michael Feingold, including Charles McNulty and Tom Sellars, have celebrated his astonishing critical voice and writing. Michael helped to challenge and shape our theater, offering new ways of interpretation and shattering existing expectations for what the critic’s role might be.

I admired Michael’s The Village Voice commentary and was inspired by it over the years. I was not alone; he won two George Jean Nathan Awards. But it was my encounters with Michael the Dramaturg, the Translator, the Playwright that had the most impact on me.

I was already familiar with the legendary Michael Feingold before meeting him in 1979, when Joel Schechter (my primary dramaturgy mentor), and I did an interview with him and Alvin Epstein for Yale Theater Magazine. Michael was a veteran new play dramaturg at the O’Neill Conference and the first Literary Manager of the Yale Rep whose script reports I had read and absorbed as a student and Assistant to the Literary Manager at Yale Rep.

When we interviewed them, I was terrified. Michael was a major force in the theater: he was The Guthrie’s Literary Manager following in the footsteps of John Lahr, Barbara Fields, and Anthony Burgess. But Michael was gracious, respectful, eager to help us, even though I was just a student at Yale. Throughout my decades long career that followed, Michael continued to be a towering force as critic, but his plays and translations permeated the theater world, where I was privileged to read and pitch them from The Guthrie, to Seattle Rep, Yale Rep, Arena Stage, and Alley Theater as a Dramaturg.

He was famous for his translations of Brecht’s The Three Penny Opera, and The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, Frisch’s The Firebugs, but there were others of consequence as well.

My favorite moment with Michael was in Seattle in 1991 at the prestigious International Festival of Arts and Ideas. I was working at Seattle Rep when he asked me to direct a staged reading of the American premiere of his extraordinary translation of Heldenplatz (Heroes Square) by Thomas Bernhard. Years before, I had briefly flirted with writing my thesis on Bernhard. He was known as the “Jonathan Swift of Austrian theater,” and Michael was the perfect unflinching theatrical sensibility to encounter Bernhard’s controversial play, which had created a scandal when it first appeared. Michael learned about my fierce interest in Bernhard, and our conversations led him to trust me to cast this controversial play. It takes place in Vienna 50 years after Adolf Hitler and the Nazi’s were welcomed in that Square. Bernhard’s play explores how antisemitism and nationalism still lies in the shadows waiting for a new day and that as one character says “There are now more Nazis in Vienna than in 1938.” In one of the lead roles, I cast the venerated film and stage actor William Biff McGuire, who had been present as a military correspondent at the Nuremburg Trials. As I write these words on the second anniversary of the January 6th Capitol Insurrection, I’m struck by Michael’s prophetic instincts. The conversations in rehearsal with Michael and the actors on antisemitism with the dangers of nationalism, and his challenging us rigorously daily to face what may be lurking in our own society, all echoes forward in time now for me. Michael Feingold’s greatest gift as an artist and critic was leaving us no place to hide, and in doing so leaving us more sober and yet more hopeful for the future.

Mark Bly

In the summer of 2014, Michael Feingold swanned into the conference room at the O’Neill Theater Center with a slow gait and determined gaze. This was the summer when I sweltered and enthused as a National Critics Institute Fellow (covered in American Theatre by cohort colleague Suzy Evans). In a sweaty room, at a table that sat 12 or more with several additional folks squeezed around the edges, we settled in for our day with “La Feingold.”

Summer 2014 of the Critics Institute was the first chaired by current head, Chris Jones, after many years of the program being led by others. As the new chair found his footing, folks came through who had been holding sessions for years, the old guard, along with newer voices to mentor us. Feingold was battling his way that summer through feeling a bit out of sorts as an older voice, and we all felt it. Along with his dyspeptic approach toward us that day, in the end, wisdom shined through.

Later that year, my first introduction to Feingold was augmented by several hours of conversation that showed me a gentler side of his wisdom and life’s story. In a long afternoon conversation with Michael, as part of many such conversations with author Jeffrey Sweet for a project on the history of the Yale Repertory Theatre, we listened to his thoughts on art, theater, and how he ended up at Yale. Feingold recalled that he had asked Robert Brustein for a recommendation on his application to Yale as a playwright when he graduated from Columbia, just before it came out in the press that Brustein had been named as the new dean of the Yale School of Drama. To paraphrase what Michael told us that afternoon long ago, Brustein wrote the recommendation then accepted his own excellent advice.

From his seat in an overstuffed armchair, within a body hampered by ill health, a sparkling mind shone that day, full of his own history, the history of Yale, dramaturgy, and all things theater. Feingold filled in the gaps in our knowledge and offered surprising observations about events of the distant past and the current theater scene.

Feingold: a conundrum and great contributor to the theater.

Martha Wade Steketee

Read more about Michael and his work here: